Photography is teaching me to see our surroundings differently… enriching peak experiences beyond my wildest dreams.

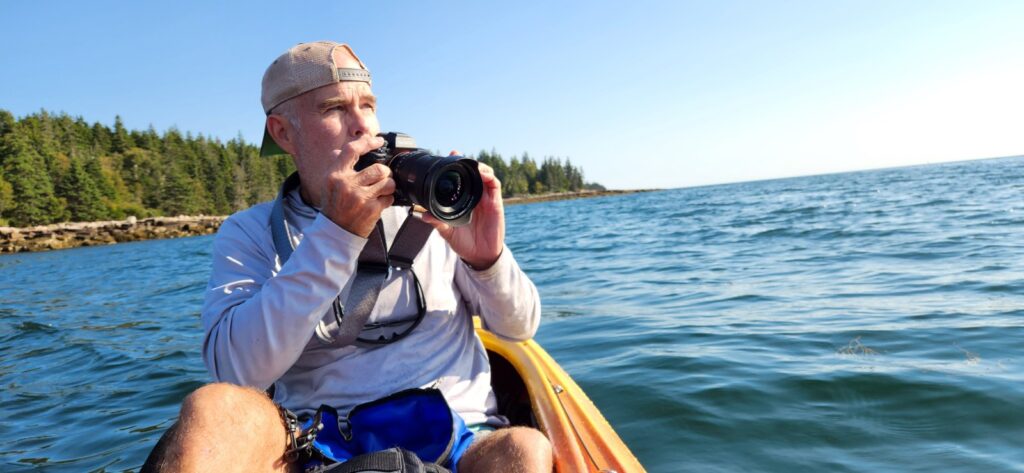

Finding intimate landscapes in remote areas, far away from crowds and off the beaten path gets me up at 4am… or in many cases puts me to bed at 4am… while chasing the best light for my photographs. Whether it’s discovering forest service roads in my 4WD overlander, kayaking into hidden lakes and rivers, or hiking to a remote waterfall. I’ll even break out the mountain bike for quicker access to a hidden gem. Chasing the best light both challenges and excites me.

Seeking The Great Light

“Capturing the radiant essence of the great light one photographic experience at a time…”

Thirty plus years photographing products and editing images for my businesses’ website design has taught me that photography is usually a compromise. That compromise centers around the light that is available in the scene that you are experiencing… Not enough of it – too much of it – too direct – not diffused – the wrong color – too uneven – too dappled – too much variance between the bright and dark areas… and on and on…

This variance between the brightest and darkest areas in a scene is what photographers call Dynamic Range, and this is the most challenging aspect in landscape photography. It’s not like we can carry a whole set of studio lights out to the scene. The human eye has twice the dynamic range of the best camera ever made. Our eyes have evolved to see the obscure details in the dark and bright areas outdoors at the same time… even at the subconscious level. The good news is that this detail is there within the RAW digital data. However, the most advanced cameras in the world can’t detect the details within both of ends of the dark / bright spectrum at the same time, within one snapshot.

Often, the greater the this dynamic range, the more dramatic and emotional the experience.

Global camera adjustments exposing the details in the dark areas, only blow out the bright areas to become an indistinguishable, pure white. Conversely, adjusting the settings for the bright areas, turns the dark areas solid black. Of course there are techniques to counter this. For example, taking multiple images from the exact same position on a tripod at different camera settings, then merging them all together in software like Photoshop. This is known as bracketing, and I do this often. However, it’s better to try and capture the best light in the first pace, even when using these multiple image bracketing techniques.

This best light is fleeting, but it is our best shot of capturing as much of these details as possible. Usually… the best light is captured right before the sun comes up, and right before the sun goes down – while most people are either sleeping or enjoying dinner. During imperfect light situations photographers can “do what you gotta do” and compromise their camera settings in order to capture “as best you can”. These compromises don’t always make for the best quality photographs and I haven’t seen any AI tools that can really fix this properly… yet anyway. For sure, these thirty years have taught me one thing… It really is all about the light!

My goal for capturing intimate landscapes is to seek this great light and share these peak experiences with you. Being out in nature can be powerfully emotional… if we quite our minds and breathe it in. Our cameras rarely capture this experience and how we felt. Often, my emotions at the time of the experience will even enhance what I am seeing. For me this is extremely spiritual. The above mentioned photographic challenges often get in the way of sharing my experience. Starting with good light is only half the battle – the other half uses Photoshop to convey my feelings. Photoshop is an extremely powerful and complex platform that enables me to convey what I felt in the most intimate way. Is it real? Is it cheating? Is it art?

*If you think about it, nothing about a digital or printed image is “real”. That reality is now a thing of the past, just a memory in my mind. My hope is to share this memory and convey the feelings that I experienced with you.

Thanks for visiting,

Greg Bright

*Note: I shoot 100% in the RAW file format – not JPEG. JPEG files are what we can see or “view” with our eyes on various electronic screens. I do not allow the camera’s software to convert my RAW files into JPEG files. I convert my RAW files to JPEG image files back in the studio.

At their core, all digital cameras start with some sort of data (Bits & Bytes / Ones and Zeros). The RAW file format is the gold standard of these bits and bytes.

At some point, the software in any digital camera can convert this raw “data” into a JPEG image file so that we can view it. Weather that’s viewing it on the back of the camera screen, or viewing it on our computer monitor, phone, or tablet. The camera uses the EXACT same concepts that Photoshop uses to “make decisions” about how to best “convert” this RAW data into a pretty JPEG for us to view… and it does a fairly good job. Of course, this is a very simplistic explanation of the sophisticated processes going on, but it will do for our purposes. Also, the initial camera settings that a photographer chooses has a lot to do with the camera’s conversion decisions.

However, the camera’s software is deciding what is “real” for you to view. Most professional photographers prefer to make these decisions themselves. Using some sort of photo editing platform like Photoshop. Relying on the preset, “baked-in” camera manufacturer’s decision making process rarely makes for a great photograph. For sure, the camera’s software will not do a very good job of conveying the emotions and feelings that I experienced out in the field. In the end, it’s all art anyway.